Understanding MutationObserver

MutationObserver is a JavaScript API that helps us watch any changes being made to the DOM. These changes will be discussed below. Here’s how to use this API:

- Create a new object using the MutationObserver constructor.

const observer = new MutationObserver(callback);

This object can be named anything. But variable names like listObserver, classObserver, etc are more intuitive. - Create a callback function that will execute when the DOM changes.

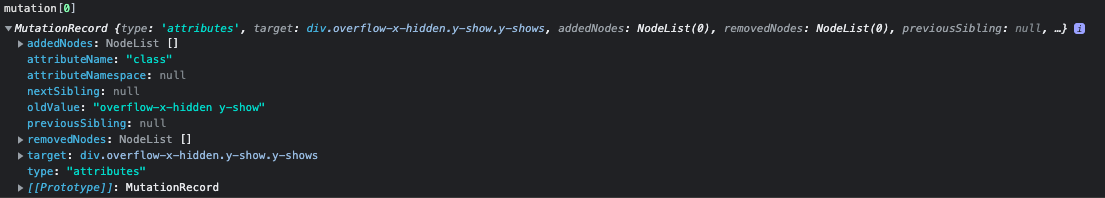

This callback function is passed in the above constructor and will only execute AFTER the DOM changes. The mutations argument is a MutationRecord (an array of all mutations that happened) which you can check inside for more data on the exact changes that were monitored. The callback function doesn’t execute by default when no mutation has been observed. The execution will depend on what we are observing, discussed in the next points.

function callback(mutations) { console.log('Children length has changed'); } - Figure out the target element that we need to observer.

- Figure out what all options do we need to observe of that target element.

- Call the observe() of the observer object.

observer.observe(targetNode, options);

Options we can observe

The second argument of the observe() method allows you to specify options to describe the MutationObserver.

let options = {

childList: true,

attributes: true,

characterData: false,

subtree: false,

attributeFilter: ['attr1', 'attr2'],

attributeOldValue: false,

characterDataOldValue: false

};

You don’t need to use all the options. However, to make the MutationObserver work, at least one of childList, attributes, or characterData needs to be set to true, otherwise the observe() method will throw an error.

childList

Set to true to monitor changes in children length.

For eg, a childList mutation occurs on an <ul> in the DOM if an <li> is added or removed from it. The amount of children the <ul> had has mutated.

attributes

Set to true to monitor changes in the attributes of an element.

For eg, an attributes mutation occuers when

<nav class="nav_fade_in"> is changed to <nav class="nav_fade_out">

characterData

Set to true to monitor changes in the character data i.e. the text inside the node

subtree

Set to true to extend the MutationObserver to all the descendent nodes of the target element.

For eg, setting attributes and subtree to true for a <ul> will monitor not only the attributes of this <ul> but also it’s direct children <li> and their children and their children and so on. \

attributeFilter

This is an extension of the attributes option. It specifies all the attributes to be monitored in an array.

For eg, if you want to monitor changes in the style attribute but not other attributes like class, you would set the option as

attributeFilter: ['style'].

It montiors all the attributes by default.

attributeOldValue

Set to true to record the previous value of any attribute that changes when monitoring the target node for attribute changes.

characterDataOldValue

Set to true to record the previous text of the target node before characterData mutation. Can you tell how to differentiate from attributeOldValue in MutationRecord?

How to find the right target node?

Now that we know how the options work, we can figure out what kind of element should we observe.

Let’s checkout the following example:

<section id="A" class="container">

<h3 id="B" class="heading show"> Section Heading </h3>

<p id="C" data-type="section-para">This is para</p>

<ul id="D" style="position: relative;">

...

</ul>

</section>

If we need to observe when #B is removed and rendered again, we can’t add Mutation Observer on #B itself. Mutation Observer is like an event listener. If the element is removed, the observer will also be “removed” and won’t exist if that element is re-rendered.

Instead, we can add an observer on the parent element, #A for childList and check whether #B exists or not.

If we only need to observe mutation in class of #B, we can simply add our observer on it, but what if we need to observe class of #B and characterData #C?

We can use the same observer variable and add #C as the targetNode in observe() and pass different options for characterData. Same observer can be added to multiple target nodes with different options, but the callback for all of them will be the same.

Now what if we wanted to observe #B, #C, and #D?

Besides adding 3 different observes separately, we also have the option to add a single observer on #A with the option subtree: true . But this extends the observer to #A and all the ‘<li>’ descendants of #D. You will need to confirm that this doesn’t cause the callback function to be called due to some other mutation, when it wasn’t supposed to be as it can lead to bugs.

Stop Observering

Once you are done with your changes defined in your callback function, and have no need to monitor the DOM anymore, you can stop the MutationObserver using observer.disconnect();

so that none of its callbacks will be triggered any longer.

The observer can be reused by calling its observe() method again.

As said before, if the element being observed is removed from the DOM, then subsequently the MutationObserver is likewise deleted due to the browser’s garbage collection mechanism.

Understanding optiReady()

optiReady is a custom function built here at OptiPhoenix using the MutationObserver API. Here’s an IIFE which defines optiReady and attaches it to the window object.

(function (win) {

'use strict';

var listeners = [],

doc = win.document,

MutationObserver = win.MutationObserver || win.WebKitMutationObserver,

observer;

function ready(selector, fn) {

// Store the selector and callback to be monitored

listeners.push({

selector: selector,

fn: fn

});

if (!observer) {

// Watch for changes in the document

observer = new MutationObserver(check);

observer.observe(doc.documentElement, {

childList: true,

subtree: true

});

}

// Check if the element is currently in the DOM

check();

}

function check() {

// Check the DOM for elements matching a stored selector

for (var i = 0, len = listeners.length, listener, elements; i < len; i++) {

listener = listeners[i];

// Query for elements matching the specified selector

elements = doc.querySelectorAll(listener.selector);

for (var j = 0, jLen = elements.length, element; j < jLen; j++) {

element = elements[j];

if (!element.ready) {

element.ready = [];

}

// Make sure the callback isn't invoked with the

// same listener more than once

// due to other mutations

if (!element.ready[i]) {

element.ready[i] = true;

// Invoke the callback with the element

listener.fn.call(element, element);

}

}

}

}

// Expose 'ready'

win.optiReady = ready;

})(this);

optiReady vs MutationObserver

As read previously, if the element is re-rendered on a dynamic site, any events or observers on that elements are removed. This is where the optiReady comes in. OptiReady adds a mutation observer on the HTML tag itself. Because this HTML tag only is rendered on the page refresh, it can help us check when new selected elements are re-rendered even on dynamic sites. But this also makes it a heavier function as it is observing the whole HTML.

How to use optiReady

The IIFE code above only defines the function. Let’s take a look at how we use it:

window.optiReady('.selector', function (ele) {

callback(ele);

});

As the function is added to the window object, it is a good practice to use it as window.optiReady. We pass a selector as a string in the first arguement and a callback function as the second arguement which will run after each time the selector elements are re-rendered on screen.

The selector we pass in optiReady checks for all the elements on the page that may match that selector. This means that for each element that exists that matches that selector, the callback function will run on their render. This means the callback function may run multiple times.

Dynamic Content loops with optiReady

For all the elements for which the callback is called, we can check them using the arguement ele in the callback example above. ele represents the current element that is re-rendered and matches the selector passed in optiReady.

Because the optiReady function loops around all the newly rendered items itself, we don’t have to use a for loop in the callback for other elements of that selector.

Let’s consider the following scenario:

<ul class="custom-list">

<li>This is it</li>

<li>This is not</li>

<li>This might be</li>

.

.

.

...

</ul>

On scroll, <li> are dynamically generated and we are adding an image to each the list-item. Here’s how we would use the optiReady function to do the same.

function prependImage(ele) {

ele.insertAdjacentHTML('afterbegin', '<img src="//op-ffm.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/conversion/ART/1.2/download-icon-yellow.svg">');

}

window.optiReady('.custom-list li', function (ele) {

prependImage(ele);

});

If we add a loop inside optiReady for the same elements, it will run n2 times so it is advised not too. Another benefit of using optiReady is that it only runs the callback for the newly rendered elements. Previously rendered elements which already have an image added to them won’t have another image added to them till they re-render. If they re-render, they will (in most cases) re-render without the image. Then the callback will add an image to them. However, unless the content is being dynamically generated, it is not advised to use optiReady as it is a heavy function compared to a normal for loop and shouldn’t be used as a normal everyday alternative.

optiReady vs waitUntil

Here’s how the waitUntil function looks:

function waitUntil(predicate, success, error) {

var int = setInterval(function () {

if (predicate()) {

clearInterval(int);

int = null;

success();

}

}, 50);

setTimeout(function () {

if (int !== null) {

clearInterval(int);

if (typeof (error) === 'function') {

error();

}

}

}, 20000);

}

Even on some static sites, there may be some dynamic content. This dynamic content may load after an event callback. Now, waitUntil function waits for 10-20 seconds only for the given content so that it can call the callback function. However, the event callback is not necessary to be called within that 10-20 second time period. For example, a user might be away from the system for a minute and may trigger the event after they are back but till then waitUntil has already stopped waiting. waitUntil runs after every 50 miliseconds to check if the conditions are met, or dynamic content is there before it can call the callback function. This is where optiReady comes in. It is only called when there is mutation in HTML. It doesn’t keep checking like waitUntil. And as it isn’t stopped till the page is refreshed, it can wait for infinite time for the dynamic content.\

Normally for our code, we have to wait for the elements to exist using waitUntil before we call the callback function. However, as optiReady is attached to the HTML itself, it is already loaded when we call the optiReady function. Hence, we don’t need to call optiReady inside the waitUntil function as the callback only runs after the given selector is rendered.

Video Session

Here is a dev session by one of the developers explaining the above concepts with examples and more tips.